Disclaimer

While it should be common sense, just in case someone doesn’t understand this: you should not blindly listen to a post on the internet on how to pay your taxes, do accounting, or even trade for that matter. Doing any of those actions wrong may result in you harming your finances and/or becoming legally liable if you e.g. misstate your income on tax forms. I’m neither a professional accountant, tax advisor nor lawyer. The content of this post is meant to be educational and should not be considered professional advice of any kind. If you intend to apply anything from this post do so at your own risk and consult a professional as this post almost definitely contains errors and oversimplifications.

Intro

This blog post will give you a practical introduction to accounting in the context of DeFi.

I’ve created this post to share some of my learnings as an amateur, self-taught bookkeeper and expand the community of accounting-interested DeFi users. Hopefully, I can help some of you with your daily crypto / DeFi trading activities. 😄

Reasons To Learn Basic Accounting

Before diving into the actual content I wanted to lay out some reasons why you might want to learn the basics of accounting if you’re not already motivated / interested. If you already know why you want to learn feel free to skip to the next section.

- Tax Compliance 🥸: If you want to easily and accurately determine your income you need a consistent system

- Tax Avoidance 😎: If you want to save on taxes you need to understand your tax laws and how you can legally leverage them to your benefit

- Insight & Understanding 📊: Accounting allows you to notice and quantify trends in your finances as well as understand how you’re spending and earning it if you want to be able to optimize something you have to be able to measure it first

- Unique mental model 🧠: If you’re a DeFi smart contract developer or auditor understanding the basics of financial accounting can give you a unique way of modeling value changes and transactions in protocols, adding another useful mental model to apply to protocols.

The Downsides Of An External Accountant

While you could hire an accountant to do everything for you, unless you have a pretty sizable net worth it will hardly be worth the cost. Most accountants are not familiar with crypto let alone obscure DeFi protocols. If your activity consists of more than just basic spot trades you’ll likely have to spend time, money, and effort explaining to a normal accountant how the different DeFi protocols, farms, NFTs, and airdrops work.

Furthermore not having direct control of your “books” (accounting lingo for where all your transactions, inventory, etc. are kept track of) limits your ability to optimize your taxes, making you completely reliant on advice from your accountant or other advisors.

💼 Crypto Tax Software & When To Get Help From Experts

While this whole post is about accounting basics and how to easily keep track of one’s books there are situations where you can and probably should consult with an expert. When it comes to filing tax statements for your yearly/quarterly reporting or better understanding the tax laws and how they apply to your specific situation you should definitely consult professionals.

In fact, if you’re just doing basic trades on exchanges and the popular DeFi protocols you should probably just use one of the many existing crypto tax software. They’ll save you a lot of effort by automating the importing and classification of transactions.

My approach is to do the accounting myself while consulting a tax advisor on the general laws and how they might apply to my situation. When it comes time to report my taxes I also compile a bunch of summaries from my accounting and hand it over to the tax advisor for them to double-check and submit the necessary tax statements in a proper manner.

🫘 Beancount

Beancount is an open-source, easy-to-use text-based accounting tool. Unlike commercial accounting programs, its base feature set is relatively limited. While this may sound like a downside I think this is actually very useful as it makes it easy to use without getting distracted by overviews, charts, and features I don’t need.

While Beancount is simple at its core you can choose to make it as sophisticated as you want by installing and/or writing your own plugins or by simply leveraging the command-line tools that come along with beancount. Beancount has a very nice API making it easy to extend with Python.

Furthermore, as part of its core feature set, it has some very nice handling of inventory or as it prefers to call it in its documentation “commodities”. While not specifically made for crypto it’s very well suited for accounting crypto transactions.

Installation

Installing beancount is very simple, but it requires you to have Python and its package manager pip already installed. If you don’t have those already I’d recommend just doing a quick search “how to install python and pip on (windows / mac / linux)”. If you’re on a Linux distro, Python and pip may already be installed so just check. Once pip is installed you can install beancount by running the following in a command line:

1

pip install beancount # or pip3 install beancount

Next to beancount I’d highly recommend also installing the fava web interface for beancount. It allows you to have a visual interface in your browser to see your finances and even allows you to make basic entries. To install fava run pip install fava.

✏️ Editing Files

Beancount and the CLI (command line) tools that come installed with it are mainly there to help you gain insight and create summaries based on your entries. Beancount entries are tracked in .beancount files which are created and edited manually, the .beancount format is a simple, human-readable text format for accounting financial data. For editing such files I’d highly recommend using an editor like VS Code, while it’s typically used by programmers note you don’t need to know how to code to be able to use beancount.

If you choose to go with VS Code you should install the Beancount plugin, it’ll give you syntax highlighting, auto alignment, auto-completion, and more to make it even easier to manage your entries.

📚 Accounting Basics: Double-Entry Bookkeeping

Now that we’ve installed the tool I’ll be demonstrating the accounting concepts, how they relate to crypto / DeFi accounting and how to apply them using beancount.

🗒️Your First Ledger

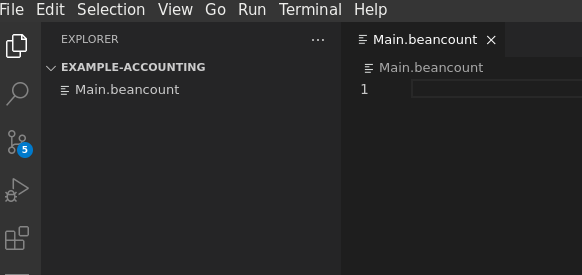

Your “ledger” or “books” is the central store of all your transactions. In beancount it’s a set of files with the .beancount extension. Let’s go ahead and create our first ledger, I’ll call it Main.beancount but the name doesn’t really matter:

If you just want to make a small note or remark for yourself you can add a so-called comment by prepending the line with a semi-colon ;:

1

2

; This is a comment

; Doesn't matter what I say here beancount won't recognize it and it won't break my file!

Next you’ll want to specify your base currency, unless you’re a DAO that wants to do its accounting in a stablecoin or crypto coin like ETH or BTC you should pick your the fiat currency you use day-to-day and report your taxes in. While I don’t live in the US for the sake of this post I’ll go with US-Dollars:

1

2

; Defines the base currency (remember this is a comment):

option "operating_currency" "USD"

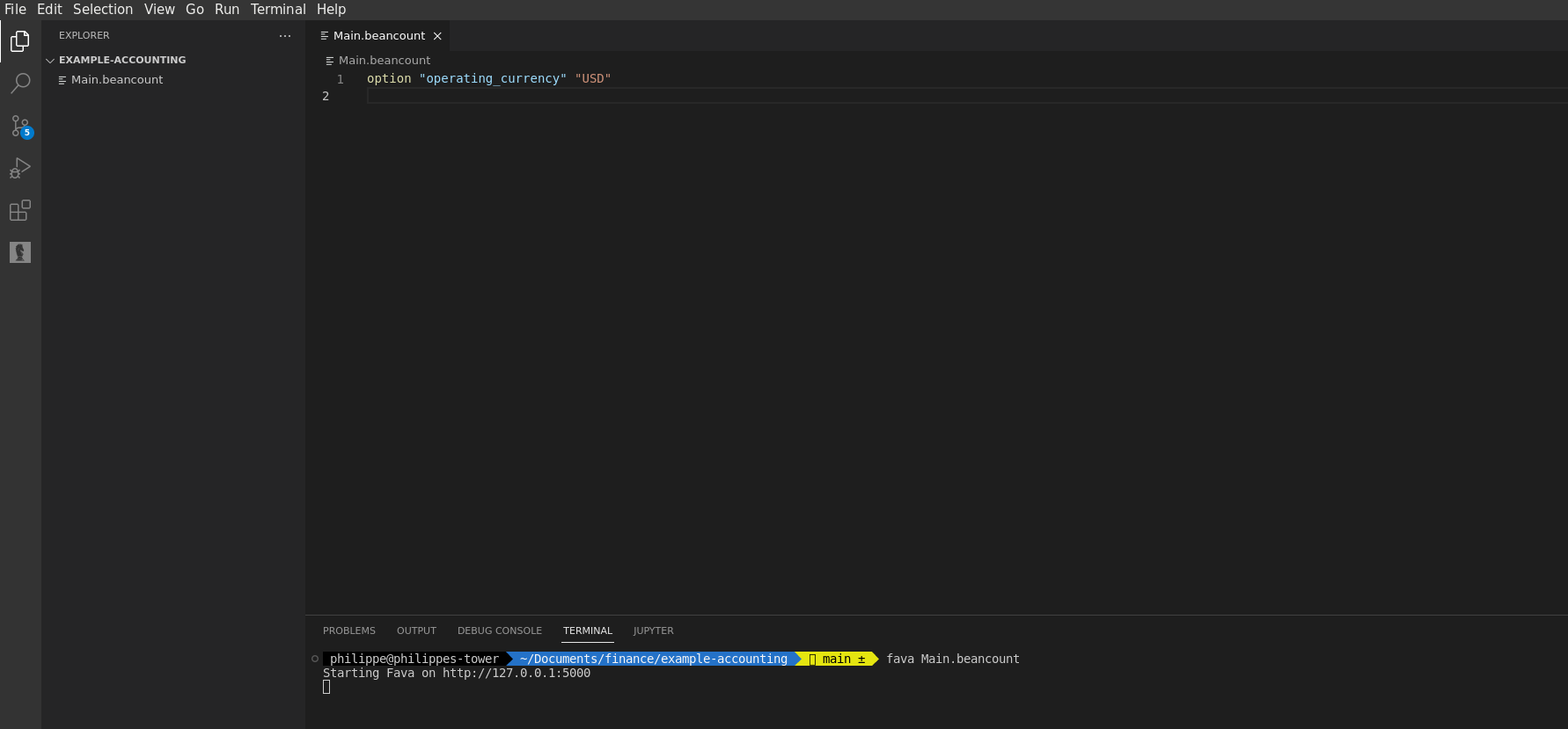

Now that the bare basics are set up you can start fava by opening a terminal and running fava Main.beancount in the folder your ledger is in:

You can then go to the shown address (likely https://localhost:5000) in your browser to get a visual overview of what you’re changing, but ignore it for now because your ledger is empty.

Transactions & Accounts

In double entry accounting, a transaction is recorded anytime an event persistently changes your finances e.g.:

- A cash transfer from one bank account to another

- Purchase of an item with a credit card

- Receiving a bill

- Buying 100$ worth of ETH

- Receiving interest

- Paying a bill you received 2 months ago

The “receiving bill” example may be an unintuitive one, how does “receiving a bill” affect my finances? Well when you receive a bill you’re being made aware of money you now owe someone. While this post is aimed at DeFi accounting these examples are meant to demonstrate what transactions roughly represent in the double-entry accounting framework.

Let’s add a simple transaction to our ledger denoting a $500 transfer from a “Bank A” to “Bank B”:

1

2

3

2022-12-18 *

Assets:Bank-A -500.00 USD

Assets:Bank-B 500.00 USD

A transaction in beancount starts with a date in iso format <year>-<month>-<day> and a *. It’s then followed by rows of postings, which each posting affecting a specific account. You can also add an optional “payee” and “narration” explaining where and what you’re doing, they must be in quotes. For example:

1

2

3

2022-12-18 * "JP Morgan" "Rebalancing to my Chase account"

Assets:Bank-A -500.00 USD

Assets:Bank-B 500.00 USD

This will help you later understand what a transaction is and why it was done so it’s highly recommended you add at least narration to your transactions. The payee and narration must always be in quotes ".

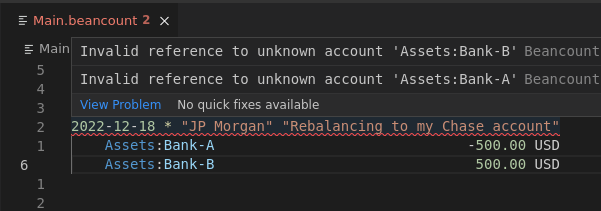

If you’ve saved your file and have the VS Code plugin or fava running you’ll notice they’re complaining about errors in your ledger file (note I have relative line numbers on which is why they look weird on my end):

This happens because beancount needs you to define the accounts you’re going to use, this requirement helps you easily catch typos later. To define an account use the “open” directive, the errors should disappear:

1

2

3

4

5

6

2022-12-18 open Assets:Bank-A

2022-12-18 open Assets:Bank-B

2022-12-18 * "JP Morgan" "Rebalancing to my Chase account"

Assets:Bank-A -500.00 USD

Assets:Bank-B 500.00 USD

You can call accounts whatever you’d like, colons : in the name are similar to the slashes / in file paths, they denote “parent” accounts, like folders allowing you to group together related accounts:

1

2

3

4

5

2020-12-18 open Assets:Cash:JPM:Savings

2020-12-18 open Assets:Cash:JPM:Checking

2020-12-18 open Assets:Cash:BofA

2021-03-11 open Assets:Crypto:Tokens

2021-03-11 open Assets:Crypto:Stables

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

// running `bean-report Main.beancount accounts | treeify`

-- Assets

|-- Cash

| |-- BofA

| |-- JPM

| |-- Checking

| |-- Savings

|-- Crypto

|-- Stables

|-- Tokens

Transactions can have more than two postings however, meaning you can express transactions that change more than 1 account:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

; Opening (doesn't have to on the same day)

2022-12-18 open Assets:Cash:Bank-A

2022-12-18 open Assets:Cash:Physical

2022-12-18 open Expenses:Fees:Bank-A:ATM

; Transaction

2022-12-18 * "Bank A" "ATM Withdrawal"

Assets:Cash:Bank-A -502.20 USD

Assets:Cash:Physical 500.00 USD

Expenses:Fees:Bank-A:ATM 2.20 USD

🪨 Balance

A core rule of double-entry accounting which is also strictly enforced in beancount is that all transactions must balance. Specifically they must balance to zero. It’s this rule combined with the use of different account types that makes double-entry accounting so powerful. It ensures that everything is kept track of in some way or another, if you create a transaction that doesn’t balance beancount will give you an error.

However to make your life easier beancount allows you to omit the value of one posting and will balance the transaction for you automatically:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

; Opening (doesn't have to on the same day)

2022-12-18 open Assets:Cash:Bank-A

2022-12-18 open Assets:Cash:Physical

2022-12-18 open Expenses:Fees:Bank-A:ATM

; Transaction

2022-12-18 * "Bank A" "ATM Withdrawal"

Assets:Cash:Bank-A -502.20 USD

Assets:Cash:Physical 500.00 USD

Expenses:Fees:Bank-A:ATM

You can check the filled in values in fava under “Journal” or by running bean-report Main.beancount print in your command line (bean-report is one of the CLI tools automatically installed alongside beancount).

Account Types

If all transactions must balance then “how do I account for income, expenses, purchases from debt or even assets I already had when I started?” you may ask. That’s where the different account types come in.

In double-entry accounting, accounts are not only where money is (asset accounts) but also where it comes from (income accounts), where it went (expense accounts), where it’s going to go (liability accounts) and where it has come from in the past (equity accounts).

These 5 base types: Assets, Income, Expenses, Liabilities and Equity are also enforced by beancount. Any valid account name must start with one of these as its root.

Assets & Liabilities

Assets and liabilities are opposites and the simplest account types. Asset are everything you have in your posession, even if you owe it to someone and liabilities are everything you owe someone. For example when you borrow $10,000.00 worth of coins on a lending protocol you’d book both assets and liabilities, because you’re both getting the tokens you’re borrowing but you’re creating debt:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

; Opening

2022-01-01 open Assets:Crypto:Tokens

2022-01-01 open Liabilities:Crypto

; Transaction

2022-03-01 * "Aave" "Borrow Tokens"

Assets:Crypto:Tokens 10,000.00 USD

Income:Crypto:Interest -10,000.00 USD

Similarly if you make a purchase from a credit card:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

; Opening

2022-01-01 open Liabilities:Credit-Cards:Mastercard-6969

2022-01-01 open Expenses:Living:Groceries

; Transaction

2022-06-01 * "Walmart" "Weekly food shopping"

Liabilities:Credit-Cards:Mastercard-6969 -79.20 USD

Expenses:Living:Groceries 79.20 USD

Expenses & Income

Counterintuitively income accounts have a negative balance, this is because they’re a source of funds, meaning they’re deducted when used. If you do a lot of transactions with different DeFi protocols, maybe even some freelance work and/or have a fixed job, having a good breakdown of income types by keeping track of corresponding income accounts can give you a good overview of how you made your money. Similarly expense accounts give you insight into how your money is spent.

Here are two examples:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

; Opening

2022-01-01 open Assets:Crypto:Tokens

2022-01-01 open Assets:Cash:Bank-A

2022-01-01 open Income:Crypto:Interest

2022-01-01 open Income:Freelance:Consulting

2022-01-01 open Expenses:Fees:Stripe

; Transactions

2022-03-01 * "Aave" "Withdraw Interst"

Assets:Crypto:Tokens 30.00 USD

Income:Crypto:Interest -30.00 USD

2022-03-01 * "Bob" "Payment for February"

Income:Freelance:Consulting -3,000.00 USD

Assets:Cash:Bank-A 2,972.23 USD

Expenses:Fees:Stripe

Equity

Equity accounts are the weirdest account type, they basically represent what you’d have left over if you took all your assets and paid off your debts. They’re mainly used when you start a new ledger or “close a time period”. In accounting “closing” a time period basically means reseting the income & expense accounts and moving any net profit / loss into equity:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

; Opening

2022-01-01 open Equity:Opening-Balances

2022-01-01 open Assets:Cash:Bank-A

2022-01-01 open Income:Crypto:Interest

2022-01-01 open Income:Freelance:Consulting

2022-01-01 open Expenses:Fees:Stripe

; Transactions

2022-01-01 * "Opening balances"

; inbetween transactions

2022-03-01 * "Bob" "Payment for February"

Income:Freelance:Consulting -3,000.00 USD

Assets:Cash:Bank-A 2,972.23 USD

Expenses:Fees:Stripe

I’ll go into closing a bit later.

Equity in total should be negative, if it’s positive it means you owe more than you have (Liabilities > Assets) and are theoretically insolvent.

🪙 Inventory, Lots and Booking Methods

Inventory & Lots

Now that we’ve covered the basics we can get into how to account crypto assets. You see the intuitive approach doesn’t work, while beancount accepts any type of currency for postings, not only the base currency we’ve defined if we try to book a simple trade it’ll give us an error:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

option "operating_currency" "USD"

2022-01-01 open Assets:Cash:Exchange-A

2022-01-01 open Assets:Crypto:Tokens

2022-01-02 * "Simple Trade"

Assets:Cash:Exchange-A -2,200.00 USD

Assets:Crypto:Tokens 2.00 ETH

Specifically beancount is telling us that Transaction does not balance: (-2200.00 USD, 2.00 ETH). You see when you book assets in double-entry bookkeeping you book them at cost, like this the transaction balances in USD:

1

2

3

2022-01-02 * "Simple Trade"

Assets:Cash:Exchange-A -2,200.00 USD

Assets:Crypto:Tokens 2.00 ETH {1,100.00 USD, 2022-01-02}

The price and date are denoted in the curly braces after the asset. This tells beancount that while we’re getting ETH we’re just converting $2,200.00 into $2,200.00 worth of ETH so that the transaction balances. Similar to the postings auto-balance you can leave out the date and/or the price and beancount will automatically fill it in for you (if you’re only buying one asset):

1

2

3

2022-01-02 * "Simple Trade"

Assets:Cash:Exchange-A -2,200.00 USD

Assets:Crypto:Tokens 2.00 ETH {}

Booking an asset or “commodity” as beancount likes to call it, like this creates a “lot”. A lot is a single acquisition / coin in your inventory. As you do multiple purchases and sales you will accumulate different lots each with their own cost and date.

In beancount lots also have an optional label which I use for NFTs:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

2022-01-01 open Assets:Cash:Exchange-A

2022-01-01 open Assets:Crypto:NFTs

2022-03-02 * "NFT Purchase"

Assets:Cash:Exchange-A -10,000.00 USD

Assets:Crypto:NFTs 1 GOBBLER {2,000.00 USD, "id:401"}

Assets:Crypto:NFTs 1 GOBBLER {2,000.00 USD, "id:402"}

Assets:Crypto:NFTs 1 GOBBLER {2,000.00 USD, "id:403"}

Assets:Crypto:NFTs 1 GOBBLER {2,000.00 USD, "id:404"}

Assets:Crypto:NFTs 1 GOBBLER {2,000.00 USD, "id:405"}

The label has to be part of lot data in the curly braces, separated by a comma and in quotes. What’s in quotes is entirely up to you, I just like to use the id:<token ID> convention. While it’s very well suited for crypto you can also use beancount’s lot system for other assets:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

2022-01-01 open Assets:Cash:Bank-A

2022-04-20 open Assets:Real-Estate

2022-04-20 open Liabilities:Mortgages:Home

2022-04-20 * "Closing the purchase of new home"

Assets:Cash:Bank-A -50,000.00 USD

Liabilities:Mortgages:Home -450,000.00 USD

Assets:Real-Estate 1 PROPERTY {500,000.00 USD, "42th Avenue 69th Street, 10019 NY"}

If you want to see your full inventory you can go to fava under the Holdings tab. I don’t like that overview too much however so I made this custom query you can run under fava’s Query tab or using beancount’s bean-query tool:

1

2

3

4

SELECT account, cost_date, sum(units(position)) as units, sum(cost(position)) as cost_total, cost_label as label

WHERE currency != 'USD'

GROUP BY currency, account, cost_date, cost_label

ORDER BY account, currency, cost_date

Booking Methods

(source)1

Now that we know how to book cryptocurrencies when we acquire we have to know how to dispose of them. The main problem or rather question here is in what order to you use your lots?

Consider the inventory resulting from the following purchases:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

2022-01-01 open Assets:Cash:Exchange-A

2022-01-01 open Assets:Crypto:Tokens

2022-01-01 open Assets:Crypto:NFTs

2022-01-02 * "Simple Trade"

Assets:Cash:Exchange-A -2200.00 USD

Assets:Crypto:Tokens 2.00 ETH {1100 USD, 2022-01-02}

2022-03-02 * "Simple Trade"

Assets:Cash:Exchange-A -3300.00 USD

Assets:Crypto:Tokens 1.50 ETH {2200 USD, 2022-03-02}

2022-06-02 * "Simple Trade"

Assets:Cash:Exchange-A -1200.00 USD

Assets:Crypto:Tokens 0.8 ETH {1500.0 USD, 2022-06-02}

| Account | Date | Units | Cost Total | Label |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assets:Crypto:Tokens | 2022-01-02 | 2.00 ETH | 2200.00 USD | None |

| Assets:Crypto:Tokens | 2022-03-02 | 1.50 ETH | 3200.00 USD | None |

| Assets:Crypto:Tokens | 2022-06-02 | 0.80 ETH | 1200.00 USD | None |

If you were to sell 1 ETH at the current price which “coin(s)” would you sell? The method by which you choose lots to be used is called the “booking method” and depends on your taxs laws. Some countries give you more freedom to choose and some less. There can also be differences between what booking rules private individuals vs. corporations can use.

FIFO (First In First Out)

The “First In First Out” booking method, dictates that the oldest lots are to be used first and is one of the most common booking methods. This method is applicable in both the US and Germany and is supported by beancount of the box:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

2022-01-01 open Assets:Cash:Exchange-A

2022-01-01 open Assets:Crypto:Tokens "FIFO"

2022-01-01 open Assets:Crypto:NFTs

2022-01-02 * "Simple Trade"

Assets:Cash:Exchange-A -2,200.00 USD

Assets:Crypto:Tokens 2.00 ETH {}

2022-03-02 * "Simple Trade"

Assets:Cash:Exchange-A -3,300.00 USD

Assets:Crypto:Tokens 1.50 ETH {}

2022-06-02 * "Simple Trade"

Assets:Cash:Exchange-A -1,200.00 USD

Assets:Crypto:Tokens 0.8 ETH {}

2022-09-13 open Income:Crypto:Gains-PnL

2022-09-13 * "not-FTX" "Sell some ETH"

Assets:Crypto:Tokens -1.00 ETH {}

Assets:Cash:Exchange-A 1,717.80 USD

Income:Crypto:Gains-PnL

The booking method is defined next to the account when it’s created. When you dispose of some assets the curly braces select which lot you’re selling. This allows you to pick specific lots / coins based on the date, cost or label. If you have a booking method configured you can leave the lot selector empty and beancount will automatically pick the right one for you and fill out the details:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

> bean-report Main.beancount print

2022-01-01 open Assets:Cash:Exchange-A

2022-01-01 open Assets:Crypto:Tokens "FIFO"

2022-01-01 open Assets:Crypto:NFTs

2022-01-02 * "Simple Trade"

Assets:Cash:Exchange-A -2200.00 USD

Assets:Crypto:Tokens 2.00 ETH {1100 USD, 2022-01-02}

2022-03-02 * "Simple Trade"

Assets:Cash:Exchange-A -3300.00 USD

Assets:Crypto:Tokens 1.50 ETH {2200 USD, 2022-03-02}

2022-06-02 * "Simple Trade"

Assets:Cash:Exchange-A -1200.00 USD

Assets:Crypto:Tokens 0.8 ETH {1500.0 USD, 2022-06-02}

2022-09-13 open Income:Crypto:Gains-PnL

2022-09-13 * "not-FTX" "Sell some ETH"

Assets:Crypto:Tokens -1.00 ETH {1100 USD, 2022-01-02}

Assets:Cash:Exchange-A 1717.80 USD

Income:Crypto:Gains-PnL -617.80 USD

Your inventory is then also adjusted automatically:

| Account | Date | Units | Cost Total | Label |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assets:Crypto:Tokens | 2022-01-02 | 1.00 ETH | 2200.00 USD | None |

| Assets:Crypto:Tokens | 2022-03-02 | 1.50 ETH | 3200.00 USD | None |

| Assets:Crypto:Tokens | 2022-06-02 | 0.80 ETH | 1200.00 USD | None |

LIFO (Last In First Out)

Similar to FIFO the LIFO rule dictates that the last lot i.e. the newest must be used first. This rule is also available in beancount and can be specified just like the FIFO rule:

1

2022-01-01 open Assets:Crypto:Tokens "LIFO"

Average Cost Booking

Unlike FIFO and LIFO, average cost booking requires you to essentially merge all lots into one at their average price. This method is used in the UK and Canada. This method is not yet supported by beancount out-of-the-box and requires manual lot recreation or writing a custom plugin:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

2022-01-01 open Assets:Cash:Exchange-A

2022-01-01 open Assets:Crypto:Tokens

2022-01-01 open Assets:Crypto:NFTs

2022-01-02 * "Simple Trade"

Assets:Cash:Exchange-A -2,200.00 USD

Assets:Crypto:Tokens 2.00 ETH {}

2022-03-02 * "Simple Trade"

Assets:Cash:Exchange-A -3,300.00 USD

Assets:Crypto:Tokens -2.00 ETH {}

Assets:Crypto:Tokens 3.50 ETH {}

2022-06-02 * "Simple Trade"

Assets:Cash:Exchange-A -1,200.00 USD

Assets:Crypto:Tokens -3.50 ETH {}

Assets:Crypto:Tokens 4.30 ETH {}

2022-09-13 open Income:Crypto:Gains-PnL

2022-09-13 * "not-FTX" "Sell some ETH"

Assets:Crypto:Tokens -1.00 ETH {}

Assets:Cash:Exchange-A 1,717.80 USD

Income:Crypto:Gains-PnL

Specific ID & HIFO (Highest In First Out)

If you’re in the US and you document your purchases very well (which is something that beancount will enable you to do), then you can apply the “Specific ID” method2. This method allows you to choose any lot from your inventory when you sell. This allows you to come up with and use essentially any booking method you want, including the HIFO “highest in first out” method. The HIFO method dictates that you sell your most expensive lots first, this minimizes your realized gains or maximizes your realized losses, allowing you to minimize your tax burden when you sell.

Selecting custom lots is supported by beancount but methods like HIFO are not supported out-of-the-box and would either have to be done manually or via a custom plugin:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

2022-01-01 open Assets:Cash:Exchange-A

2022-01-01 open Assets:Crypto:Tokens

2022-01-01 open Assets:Crypto:NFTs

2022-01-02 * "Simple Trade"

Assets:Cash:Exchange-A -2,200.00 USD

Assets:Crypto:Tokens 2.00 ETH {}

2022-03-02 * "Simple Trade"

Assets:Cash:Exchange-A -3,300.00 USD

Assets:Crypto:Tokens 1.50 ETH {}

2022-06-02 * "Simple Trade"

Assets:Cash:Exchange-A -1,200.00 USD

Assets:Crypto:Tokens 0.8 ETH {}

2022-09-13 open Income:Crypto:Gains-PnL

2022-09-13 * "not-FTX" "Sell some ETH"

Assets:Crypto:Tokens -1.00 ETH {2022-03-02}

Assets:Cash:Exchange-A 1,717.80 USD

Income:Crypto:Gains-PnL

If you’re manually selecting lots you have to make sure that your selection in the curly brackets { } is not ambiguous

Universal vs. Per Account Booking

FIFO, LIFO and HIFO all require you to keep track of inventory you can book from. While you could keep track of one inventory for every account (Exchange A, Exchange B, Wallet 1, Wallet 2, etc.) this separation starts to break down when you transfer assets between locations. That’s why for crypto it’s usually more practical to keep track of a single inventory and do “universal booking” meaning regardless where you buy / sell your assets you’re always booking from the

DeFi Accounting

Now that we’ve covered the basics, understand booking methods and how to account for basic trades I wanted to go through some more examples related to DeFi and some other smaller nuances.

Profit & Loss Accounts (PnL Accounts)

For gains related to crypto or other trading activity I create what I like to call “PnL accounts” they’re accounts where book all gains and losses of a certain type so that I can immediately see my net gain and don’t have to check whether or not a given trade realized a loss or gain:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

2022-01-01 open Assets:Cash:Exchange-A

2022-01-01 open Assets:Crypto:Tokens "FIFO"

2022-01-01 open Assets:Crypto:NFTs

2022-01-01 open Income:Crypto:Gains-PnL

2022-01-01 * "NFT Purchase"

Assets:Cash:Exchange-A

Assets:Crypto:NFTs 1 GOBBLER {4,000.00 USD, "id:400"}

Assets:Crypto:NFTs 1 GOBBLER {3,900.00 USD, "id:401"}

2022-03-01 * "ArtGobblers" "Sale"

Assets:Crypto:NFTs -1 GOBBLER {"id:401"}

Assets:Cash:Exchange-A 2,000.00 USD

Income:Crypto:Gains-PnL

2022-08-01 * "DCA into ETH"

Assets:Cash:Exchange-A -500.00 USD

Assets:Crypto:Tokens 0.482 ETH {}

; Includes Fee

2022-11-13 * "Uniswap" "Get some DAI"

Assets:Crypto:Tokens -0.202838 ETH {}

Assets:Crypto:Tokens 322.113821 DAI {1.00 USD}

Income:Crypto:Gains-PnL

This allows me to easily isolate and track my profit (or losses):

1

2

3

2022-01-01 open Income:Crypto:Gains-PnL

2022-03-01 * ArtGobblers | Sale 1900.00 USD 1900.00 USD

2022-11-13 * Uniswap | Get some DAI -111.70 USD 1788.30 USD

The above overview can also be seen in fava by clicking on “Go to account” and selecting your PnL account.

However if you want to breakdown your losses and gains into separate accounts you can do so. You could even automate the process with a plugin. Making a plugin is actually relatively easy, check out the beancount docs on how to script plugins.

Spread, Slippage & Fees

When you perform trades on exchanges, centralized or decentralized there are different factors that reduce the value you’re able to get out of a trade. By “fees” I’m referring to explicit network and/or exchange fees that are deducted from your account in exchange for facilitating the trade. Spreads and slippage on the other hand, while not the same thing, for the sake of accounting they may as well be as they both represent deviations from your practical price and the actual market price.

There are two approaches to account for these trade impacts:

- Direct accounting: calculate fees and slippage / spread and put them into respective loss accounts

- Cost basis inclusion: add any cost associated with a trade to the cost basis of the output asset

Not only is the second option simpler, the first may be incorrect depending on your tax laws. You see trading fees and price difference costs (slippage, spreads) are usually tax deductible however if you account them directly by puting them to an expense account, you’re moving forward the time of that deduction. To make it simpler let’s just look at a simple example with an exchange that charges an unrealistic 25% fee:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

2021-01-01 open Assets:Cash:Exchange-A

2021-01-01 open Expenses:Fees:Exchange-A

2021-01-01 open Assets:Crypto:Tokens "FIFO"

2021-01-01 open Assets:Crypto:NFTs

2021-01-01 open Income:Crypto:Gains-PnL

2021-06-13 * "ETH DCA"

Assets:Cash:Exchange-A -2500.00 USD

Expenses:Fees:Exchange-A 500.00 USD

Assets:Crypto:Tokens 2.00 ETH {1000 USD, 2021-06-13}

2022-07-14 * "ETH Sale"

Assets:Crypto:Tokens -0.5 ETH {1000 USD, 2021-06-13}

Assets:Cash:Exchange-A 450.00 USD

Income:Crypto:Gains-PnL 50.00 USD

Versus Cost inclusion:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

2021-06-13 * "ETH DCA"

Assets:Cash:Exchange-A -2500.00 USD

Assets:Crypto:Tokens 2.00 ETH {1250 USD, 2021-06-13}

2022-07-14 * "ETH Sale"

Assets:Crypto:Tokens -0.5 ETH {1250 USD, 2021-06-13}

Assets:Cash:Exchange-A 450.00 USD

Income:Crypto:Gains-PnL 175.00 USD

You see in the direct inclusion scenario the full expenses is booked in the first year (2021) although that loss hasn’t necessarily had a material impact yet. In the second scenario 1/4 of the fee is included as part of the loss because 1/4 of the original ETH amount is sold, the fee is implicitly accounted for when a gain / loss from the affected amount is actually realized.

Which method you can and should use really depends on your tax laws. Accounting the expense immediately can help reduce your tax bill but may also have you understate your net profit or overstate your net loss. For these kinds of details it’s usually best to consult a professional as they should be able to answer such questions quite easily and quickly if they have accounting / tax expertise.

Crypto Income

Whether it’s freelance work or interest, income denominated in crypto is relatively easy to account, similar to a trade book the crypto to your assets at the current market price and the relevant income account as source of the funds:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

2021-01-01 open Assets:Crypto:Tokens "FIFO"

2021-01-01 open Income:Crypto:Gains-PnL

2021-01-01 open Income:Crypto:Interest

2021-01-01 open Income:Freelance:Consulting

2022-03-03 * "Bob" "Payment of invoice #1001"

Income:Freelance:Consulting

Assets:Crypto:Tokens 1.7623 ETH {2,966.84 USD}

; Withdrawal of original collateral not booked because you owned it before and still own it after the withdrawal

; Only the change, the interest is accounted

2022-07-31 * "Aave" "Withdrawal of collateral + interest"

Income:Crypto:Interest

Assets:Crypto:Tokens 34.110 DAI {0.996 USD}

Be Aware Of Income Separation

Depending on your tax laws you may not be able to deduct losses from crypto against income earned from your fixed job or freelance work because they’re classed as different types of income.

This means that if you get paid in crypto and the price drops by 50% you may have to pay taxes on the full value of the originially received amount as it was personal income while only being able to deduct the 50% price fall from other crypto gains.

If you get paid in crypto it’s vital you inform yourself to what extent there’s a separation so that you can sell and set aside received crypto if necessary.

Liquidity Tokens

LP Tokens are the fungible or non-fungible (NFT) tokens you get when providing liquidity to DEXs like Uniswap, Sushiswap or Pancakeswap. The tax implications of providing liquidity is hard to determine in most of the world as there doesn’t really exist an equivalent instrument in the TradFi world that tax authorities or advisors could really compare to.

But looking at how they work we can at least try to account the intuitively:

- You give up 1 or 2 assets

- You receive another asset in return (the LP token/s)

- While you hold the LP asset it’s price can develop independently of the assets, accruing fees and going up or down in value based on the underlying

- When you get rid of the LP asset you receive 1 or 2 assets in different proprtions

Based on these circumstances I think it’s fair to say that when you provide liquidity you’re disposing i.e. practically selling your tokens for the LP asset:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

2021-01-01 open Assets:Crypto:Tokens "FIFO"

2021-01-01 open Income:Crypto:Gains-PnL

2021-01-01 open Income:Crypto:Interest

2021-01-01 open Income:Freelance:Consulting

2021-01-01 open Equity:Opening-Balances

2022-09-03 * "Opening Transaction"

Assets:Crypto:Tokens 6,000.00 DAI {1.0001 USD}

Assets:Crypto:Tokens 4.23 ETH {1,720.00 USD}

Equity:Opening-Balances

2022-11-01 open Assets:Crypto:LP "FIFO"

; price directive tells beancount about prices

2022-11-01 price ETH 1,565.00 USD

; Fee cost included

2022-11-01 * "Sushiswap" "Provide ETH / DAI liquidity"

Assets:Crypto:Tokens -3,000.00 DAI {}

Assets:Crypto:Tokens -1.90384929272910 ETH {}

Assets:Crypto:LP 629.37 SUSHI-LP {{5979.52 USD, "DAI-ETH"}}

Income:Crypto:Gains-PnL

You can indicate the total cost of the lot rather than the cost / unit by using double curly braces:

2.0 ETH {1,200.00 USD}: Book 2 ETH at a cost of 1,200.00 USD each3.0 ETH {{3,300.00 USD}}: Book 3 ETH at a total cost of 3,300.00 USD or 1,100.00 USD each

When you withdraw your underlying from your LP position you can then book the disposal of the LP asset although I’d put that into a separate LP account. Accounting this can be a bit tricky if you consider that to withdraw from your LP you’re also spending gas and therefore desposing of ETH, booking a potentially separate loss / gain:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

2022-12-04 price ETH 1,242.161 USD

2022-12-04 open Assets:Temp ; holds fee value

2022-12-04 * "Sushiswap" "Withdraw liquidity (network fee)"

Assets:Crypto:Tokens -0.003481 ETH {}

Assets:Temp 4.324 USD ; Fee value

Income:Crypto:Gains-PnL ; Profit / Loss from disposing ETH for fee

2022-12-04 open Income:Crypto:LP

2022-12-04 * "Sushiswap" "Withdraw liquidity withdrawal"

Assets:Crypto:LP -629.3700 SUSHI-LP {"DAI-ETH"}

Assets:Temp -4.3240 USD

Assets:Crypto:Tokens 3,400.0000 DAI {1.00 USD}

Assets:Crypto:Tokens 2.7375 ETH {1,242.161 USD}

Income:Crypto:LP

Note that I split the single transaction (LP withdrawal) over two entries so that I can leverage beancount’s auto-balance feature to calculate the P/L on the ETH and the LP tokens, furthermore for the sake of simplicity I’m not following my own rule of including the fee in the cost of the output.

📉 Margin & Shorting

Before proceeding with this section where I show you how I’d account margin & shorting related transactions I’d recommend you pause here, and as an exercise try to record your own or example transactions in beancount or on paper (opening a short, closing, liquidation). Break it down step by step, what am I putting into this transaction, what am I getting out? What cost basis is associated? Do my transactions balance and have I forgotten to book income / expenses?

Here I’ll talk mainly about margin, leverage and shorting in the sense where you’re actually borrowing assets to some degree. If you’re leveraged derivatives such as Perps or Inverse tokens that don’t directly require debt on your part you can use the approaches described above to account for your transactions.

Borrowing USD

The first step when leverage trading or shorting is borrowing. Borrowing allows you to basically “play with someone else’s money” paying them back once your trade was successful or degraded to the point where the funds are called back, typically in a process called “liquidation”.

Thinking of the basics borrowing has two sides: you get something (book to assets) and you create an obligation to pay something back (book to liabilities):

1

2

3

4

2023-01-01 * "Exchange-A" "Borrow 1,000 USD to margin trade"

Liabilities:Margin:Exchange-A -1,000.00 USD

Assets:Cash:Exchange-A 1,000.00 USD

Now if you trade with those borrowed assets you can book them as normal, buying and selling different cryptos, tracking the cost basis etc.

Repaying USD

Similar to the borrow transaction you simply book the same accounts but in reverse, adding a positive amount to your liabilities and deducting from your asset accounts. To account for interest you simply book an “interest expense” account:

1

2

3

4

5

2023-01-01 * "Exchange-A" "Borrow 1,000 USD to margin trade"

Assets:Cash:Exchange-A -1,003.00 USD

Liabilities:Margin:Exchange-A 1,000.00 USD

Expenses:Interest:Margin:Exchange-A 3.00 USD

Borrowing Non-Base Currency Assets

If you short crypto the old school way or are just borrowing a foreign stable coin on a decentralized lending protocol you’ll have to account your liabilities slightly differently. Since your core ledger is tracked in another asset you may actually realize a loss / gain once you repay your debt because of a difference in price. Let’s you were shorting LUNA and you borrowed and sold 1,000 LUNA at a price of 100 USD / LUNA and you later bought it back and repaid that debt after it dropped to 80 USD, that’d be a gain of 20 USD / LUNA that you have to somehow account. This can achieved by also tracking the “cost basis” of your debt this is nearly identical to what you would do for assets although a bit more counterintuitive. The “cost basis” is not the value you spent to acquire the debt but instead the value of the debt when it was created:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

2022-06-01 open Liabilities:Crypto:Exchange-A "FIFO"

2022-06-01 open Assets:Crypto:Exchange-A "FIFO"

2022-06-01 open Expenses:Crypto:Trading-Fees:Exchange-A

2022-06-01 * "Exchange-A" "Borrow LUNA for short"

Liabilities:Crypto:Exchange-A -1,000.00 LUNA {100.00 USD}

Assets:Crypto:Exchange-A 1,000.00 LUNA {100.00 USD}

2022-06-01 * "Exchange-A" "Sell borrowed LUNA"

Assets:Crypto:Exchange-A -1,000.00 LUNA {}

Assets:Cash:Exchange-A 99,987.00 USD

Expenses:Crypto:Trading-Fees:Exchange-A 13.00 USD

Note that liability accounts that track non-base currency assets also need a booking rule as you may be borrowing in several batches over time at different prices and need to know how to account the value change of your debt.

Repaying Crypto

Closing the LUNA short from above you’d book at 80 USD a transactions as follows:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

2022-07-01 * "Exchange-A" "Buy Back LUNA"

Assets:Cash:Exchange-A -80,087.00 USD

Assets:Crypto:Exchange-A 1,001.00 LUNA {80.00 USD}

Expenses:Crypto:Trading-Fees:Exchange-A 7.00 USD

2022-07-01 * "Exchange-A" "Repay LUNA loan + 1 LUNA of interest"

Assets:Crypto:Exchange-A -1,001.00 LUNA {}

Liabilities:Crypto:Exchange-A 1,000.00 LUNA {}

Income:Crypto:Debt-PnL -20,000.00 USD

Expenses:Interest:Margin:Exchange-A 80.00 USD // Value of 1 LUNA of interest just bought added to expenses

Liquidation

Liquidation is nearly identical to repayment except you may have to pay a liquidation penalty on top of the value of the now increased debt, realizing both a loss because of the appreciation of your liability and expense in the form of the liquidation penalty:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

; Alternative Universe where LUNA went to 200 USD

2022-07-01 * "Exchange-A" "Liquidation at 200 USD / LUNA + 5% penatly and 4 LUNA interest"

Assets:Cash:Exchange-A -210,800.00 USD

Liabilities:Crypto:Exchange-A 1,000.00 LUNA {}

Expenses:Interest:Margin:Exchange-A 800.00 USD

Income:Crypto:Debt-PnL 100,000.00 USD

; 5% on the 200k worth of LUNA debt

Expenses:Liquidation:Exchange-A 10,000.00 USD

Basic Tax Optimization

Now that we have the tools and some examples to account basically any crypto transaction let’s go through some tax tips that should apply to most jurisidictions. However before we dive in I’d refer you to the disclaimer and consulting professionals sections again, this is not tax / legal advice but merely educational examples of tax strategies that may or may not work or even be legal depending on where you live and file your taxes. There can be very subtle but important differences between countries based on your precise circumstances. Furthermore professional tax advisors and accountants should be able to advise on other strategies that are better or actually suited to your circumstances.

HODL & Borrow

Unless your country has some type of wealth / property tax on merely having valuable assets only realized gains are taxed. What this means is that if you buy a coin and it e.g. goes up 1000x over time turning your $ 10,000 investment into $ 10M that $ 9.99M won’t actually be taxable until you sell those coins for another or fiat.

Don’t try to avoid paying taxes by selling your coins for other coins, or spending the tokens directly on goods or services via e.g. a crypto card because most jurisidictions count any disposal as a realization of your gains. Meaning if you pay e.g. for a watch that costs 15k with coins you purchased at a value of 1.5k you’ll owe the government taxes on the 13.5k realized gain.

So great, you have coins that have gone up in value but you can’t / don’t want to sell them to avoid taxes, what’s the point of having those juicy gains if you can’t spend them, right? Well that’s where the second part comes in. Instead of selling to access the value of your assets you can borrow against them, either on exchanges in the form of margin loans, lending protocols or even directly with people OTC depending on the asset and what the amount you’re borrowing against is. In most jurisidictions this doesn’t count as a sale because you technically still own the asset, you’ve just deposited it somewhere as collateral, as long as you pay the interest and don’t default on the loan you don’t realize a gain. In fact if you have good collateral you may never have to directly repay the loan as you could continue to refinance as the value of your asset appreciates.

Example:

You have 1,000.00 ETH you bought back in the day for $ 20 a piece and you want to get yourself a nice car for $ 60k. Instead of selling that ETH you go to an institution or lending platform and deposit the more than $ 1M worth of ETH as collateral, borrowing $ 60k against it. Not only will you not realize a gain (again depends on your jurisidiction) the interest on that loan is likely very low and definitely much lower than any consumer credit card debt. A win-win.

Long-term vs. Short-term Gains

Extending the HODL & borrow strategy you can also save a lot in taxes by being aware of your long-term vs. short-term profit taxes. You see most jurisidictions have a different tax rate for profits that are made from assets that were held for shorter periods and profits from assets that were held for longer, this is meant to discourage speculation. In Germany for example, short-term gains from crypto held less than 1 year are taxed at your personal income tax rate which very easily reaches 42%. However if you hold your crypto for more than a year any gains are completely tax free (doesn’t apply to all coins though and only for private individuals not companies). The US seems to have a similar rule whereby short-term crypto sales count as a “short-term capital gain” and long-term sales count as “long-term capital gain”.3

This is why systematically tracking your crypto transactions can be very useful so that you can more easily know whether you can decrease your tax burden by simply waiting a bit longer before selling.

Tax Loss Harvesting

Tax loss harvesting is strategy whereby you strategically sell positions at a loss to offset your net gain for a year and reducing your tax burden. This can be the silver lining in the those shitty NFT and dog coin purchases, they could at least allow you to reduce your taxable gain. Selling earlier at a loss is also useful because jurisidictions that differentiate between long-term and short-term gains usually do the same for losses whereby long-term losses are only deductible from long-term gains and short-term losses from short-term gains.

Example:

It’s 2022 and the tax year is ending in 1 month, throughout the year I realized $ 5,000.00 of short-term gains taxed at 30% and $ 3,000.00 of long-term gains taxed at 10%. The cutoff for long-term / short-term is 1 year. I also still hold an NFT that rugpulled right after launch almost a year back, 350 days. At the time I bought the NFT I aped in with ETH that was at the time worth $ 2,000.00. Now there’s no trading volume, no active bids, the project is basically dead, meaning a current value of 0$ or a realized loss of $ 2,000.00 if I were to sell it.

If I don’t sell the NFT I’d have to pay 5000 x 30% + 3000 * 10% = $ 1,800.00 in taxes. If I wait too long to sell the NFT until it’s been a year since the original aquisition it’ll only count against my long-term gains meaning I’d pay 5000 x 30% + (3000 - 2000) * 10% = $ 1,600.00 in taxes. $ 200.00 In savings are good but it could be even better. If I sell the NFT immediately it would just still count to my short-term gains, reducing my tax burden to (5000 - 2000) x 30% + 3000 * 10% = $ 1,200.00, $ 600.00 in savings!

Beyond simply reducing your tax burden you can also lower the cost basis of the asset if you wish to keep it by selling and then re-buying it at a similar price, as this will realize a loss and lower your cost basis because you bought back in at a lower price. Done right this can move losses into your short-term gains and move the future gain to your long-term side.

Some jurisidictions have rules that prevent you from legally accounting losses if you replaces the asset i.e. buy back-in shortly after you sold it so it is highly advised you do some research before doing this. The US for example has a rule that prevents this called the “wash sale” rule that prevents you from accounting losses for securities such as stocks and bonds that you buy back in less than 30 days.

Trading LLC

Just create an LLC bro

As I briefly touched on before depending on your tax code different types of income may have to be accounted and taxed differently. What this can for example mean is that if you’re a freelancer getting paid in crypto the value upon receival may be taxed as normal income while a realized loss from the coin itself may only count as capital gains, the may not be able to deduct the one from the other.

This is where a “Trading LLC” comes in. In case you didn’t know in almost all jurisidictions of the world buisnesses and individuals are taxed differently and have different accounting rules that apply to them. However you don’t have to have a “real company” to be able to take advantage of the differences in rules. In most capitalist countries it’s relatively easy and not that expensive for anyone to create a buisness entity. A buisness entity is a “virtual” legal person separate from yourself as a private individual but controlled by you. Almost how a smart contract is different to an EOA / user wallet. A company is an imaginary concept, it’s a “legal ritual” that has to be enacted by you, typically together with a lawyer or notary that allow to create a new “person” in the legal system. It’s less complicated than it sounds but there are several trade-offs to consider before creating one solely for the purposes of trading:

Reporting requirements & overhead

Unlike your personal income statement filing for a company is usually more complex and expensive than just for yourself as it’s typically always done by a professional. This may not always be the case, in some countries it may easier to file taxes for a company than it is to do so privately

Laws & compliance

Trading as a company may require you to get additional licenses from regulatory bodies if it’s a “protected” or “reserved” activity in your country.

Finacial separation

While there are exceptions, buisness entities are typically separate persons with separate finances under the law so you can’t just freely transfer assets back and forth without certain tax or even legal implications.

For example, while a buisness entity may allow you to deduct gains and losses from different income streams going into the business from one another, any profits are “stuck” in the company. Legally taking money out of your business may require you to issue a dividend or salary which will be taxed as capital gains or normal income, meaning you may end up paying more taxes (corporate tax + capital gains / income tax) than you if you were to just directly trade as private individual.

KYC

Trading on exchanges and other KYC’ed platforms will also require you to do a separate registration, even more overhead.

Final Thoughts

While none of us want to pay our taxes the penalty for not doing so or doing so incorrectly can be quite severe. Understanding the basics of financial accounting and your local tax code will allow you to not only pay your taxes and sleep well at night but also give you better insight into your finances and finance in general.

I hope I was able to present the stereotypically boring subject of accounting and taxation in an engaging and valuable way. If you have any feedback or want to stay updated future finance / smart contract content you DM / follow me on Twitter.