Image: Telecom switchboard operator1

Image: Telecom switchboard operator1

Intro

Every2 smart contract on Ethereum and other EVM chains starts with its function dispatcher. Function dispatchers tell the contract whether they’ve implemented the requested method and where the code for that method is found within the contract. I’ll also refer to function dispatchers as “selector switches” as they remind of Telecom switchboard operators and are similar to switch-statements of common programming languages.

Function dispatchers are executed upon every contract call meaning inefficiencies & optimizations in this area of the code will impact all calls and the general gas efficiency of the contract. The most straightforward approaches to function dispatchers employed by high-level languages like Solidity and Vyper and even taught in the Huff tutorial on function dispatching are however not as optimal as they could be.

This post will look at the common approaches to function dispatchers and show more optimal versions you can apply to your low-level contracts. This post also assumes some familiarity with the EVM and its opcodes (low-level EVM instructions); if you need a quick intro I’d recommend Huff’s “Understanding the EVM” Tutorial section as it gives a good overview of how the EVM works.

This post will look at different ways to build function dispatchers and the different tradeoffs I considered when I built the highly optimized function dispatcher for the improved Wrapped Ether implementation METH that I’m working on.

Refresher: What Are Selectors?

Selectors are standardized 4-byte identifiers used to identify methods across contracts. Function selectors are the left 4-bytes of the keccak hash of a function’s signature. Since the data types of the parameters are also hashed this allows contracts to differentiate between functions that have the same name but different sets of parameters like the safeTransferFrom methods in ERC721 tokens. One thing to watch out for is selector collisions, these can occur because the selector is only the first 4 bytes of the actual hash, they are quite rare however, occurring mainly in CTFs. You can see an example of vulnerability arising from a selector collision in my write-up of the Paradigm CTF 2022 “Hint Finance” challenge.

Selector Example

Function:

1

2

3

function withdraw(uint256 amount) external {

// ...

}

Signature: withdraw(uint256)

Selector:

keccak256("withdraw(uint256)")[0:4] =>

0x2e1a7d4d13322e7b96f9a57413e1525c250fb7a9021cf91d1540d5b69f16a49f =>

0x2e1a7d4d

Call to withdraw(1e18):

1

2

3

4

selector: 0x2e1a7d4d

amount (1e18): 0x0000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000de0b6b3a7640000

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

calldata: 0x2e1a7d4d0000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000de0b6b3a7640000

The precise specification of how selectors are defined and computed can be found in the Contract ABI Specification, it specifies how arguments are encoded and some more precise details when it comes to actually computing the selector for different types.

If you’ve installed the foundry smart contract development framework using

foundryupyou should have thecasttool installed which lets you easily get the selector of any method by runningcast sig <your function>e.g.cast sig "withdraw(uint)"results in0x2e1a7d4d

Having a common standard for selectors is extremely useful as it lets different contracts easily interact with each other without having to look up and implement some custom data and function encoding scheme for every contract. It also allows higher-level languages to offer some abstraction in the form of public / external methods.

Micro Huff Crashcourse

Since I’ll be denoting opcode snippets using Huff in this post I’ll do an extremely brief intro to Huff, you can find a full list of Huff’s features here: docs.huff.sh/get-started/huff-by-example/.

What is Huff?: Huff is a low-level assembly language for the EVM, it’s basically just mnemonic bytecode (bytecode but written as aliases “SLOAD”, “DUP1” rather than the byte values) with some syntactic sugar around selectors, constants and jump destinations to improve the developer experience.

Opcodes: Opcodes in Huff are written in their mnemonic i.e. “word form” and can be upper / lower case. The only exceptions are the PUSH1 - PUSH32 opcodes. For these, the values can be written directly in hexadecimal and the compiler will find the shortest fitting push opcodes for them e.g. 0x3212 compiles to PUSH2 0x3213 (0x613213). Huff also allows for constants which are defined by #define constant CONSTANT_NAME = 0x<constant value> and are referenced by square brackets e.g. [PERMIT_TYPEHASH] and are also compiled to PUSH opcodes.

Jump Labels & Destinations: Jump labels are a convenient way to manage jumps without having to manually recalculate all destinations every time a bit of code is changed. Destinations are defined by <name_of_label>: e.g. withdraw_start:, the compiler will insert the 1-byte JUMPDEST opcode at all labels, whether they’re referenced or not. Jump destinations can be pushed to the stack by just writing their label: withdraw_start, Huff will currently always use a PUSH2 opcode even if the destination only requires 1 byte.

Macros: Macros are kind of like functions in higher-level languages. They’re bits of code you can reuse and are inserted inline by the compiler whenever referenced. They can also have static arguments which are also inserted at compile time. Within the macro, static arguments are referenced by angled brackets and the name of the argument e.g. <zero>. Macro arguments can be static values, jump labels or opcodes.

Other features: Huff has a few other features like fn macros, tables, helper functions and even a way to define tests but I won’t be using most of them for this post outside of tables which I’ll introduce once we start using them. You can check out the extra features with the above link to Huff’s “Huff by example” section.

Because Huff is so essentially mnemonic opcodes with bells and whistles I’ll also be using it to illustrate theoretical compiler output in a more human-readable way.

Common Function Dispatchers

The goal of a function dispatcher is to:

- Load the selector from calldata

- Reverts for non-matching selectors

- Jump to the section of bytecode that executes the logic for that function

Linear If-Else Dispatcher

“Linear If-Else Dispatcher” are the most straightforward and common dispatcher, generated by Solidity, Vyper and even presented in Huff’s tutorial. While the precise structure and opcodes used between the languages differ, an efficient Huff implementation and very similar to actual output from the Solidity compiler could look something like this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

/*loads bytes 0-31 of calldata and shifts right by 28 bytes to get the 4-byte selector

(28 bytes = 28 * 8 bits = 0xe0 in hexadecimal)*/

// In Huff it's a common convention to denote the state of the stack in a comment on every line

0x0 calldataload 0xe0 shr // [call_selector]

// 1st If-Else Block

// Copy selector from stack

dup1 // [call_selector, call_selector]

// Place selector on stack

0x01020304 // [function_selector, call_selector, call_selector]

// Compare, are they eq-ual?

eq // [function_selector == call_selector, call_selector]

// Place function destination on stack in case they match

function1_dest // [function_dest, function_selector == call_selector, call_selector]

// Conditional jump, will jump if the result from `eq` was true (1)

jumpi // [call_selector]

// If selectors didn't match `jumpi` will not jump and the code will continue here

// Next if-else blocks

dup1 0x05060708 eq function2_dest jumpi

dup1 0x11223344 eq function2_dest jumpi

...

// if no match just revert

0x0 0x0 revert

Shown as a diagram the control flow progresses step by step through every else-if “block” until a matching selector is identified or the end of the switch is reached, in which case it results in a revert:

This approach makes for a decent selector switch, it can easily be generated for any contract regardless of its selector set and count and fulfils our requirements of a selector:

- It loads the selector from calldata

- Reverts if nothing matched

- It does a direct comparison with all selectors until it finds one, won’t jump unless there’s a 1:1 match

However, this approach is far from efficient because the average gas use (assuming the functions are randomly ordered in the switch and all used equally) grows linearly with the number of functions. Assuming we’re considering the gas use as run-time complexity this would have a time complexity of $O(n)$ in classic CS big-O notation. This is fine and quite efficient for contracts with ~3-6 functions but quickly loses ground to alternative approaches as the number of functions grows.

Usage based optimization:

Without changing the fundamental approach we can optimize the average gas use by reordering the switch, putting more commonly used functions first. This will allow common calls to go through fewer if-else blocks to find their match, improving average gas performance. The problem with this optimization is that there’s no real way to tell the compilers of high-level languages like Solidity / Vyper your selector-order preference and you need to anticipate the average use of your contract which can be tricky. A practical example of this is in SeaPort, where a function name was mined such that its selector was 0x00000000 and therefore placed earlier in the function dispatcher.3

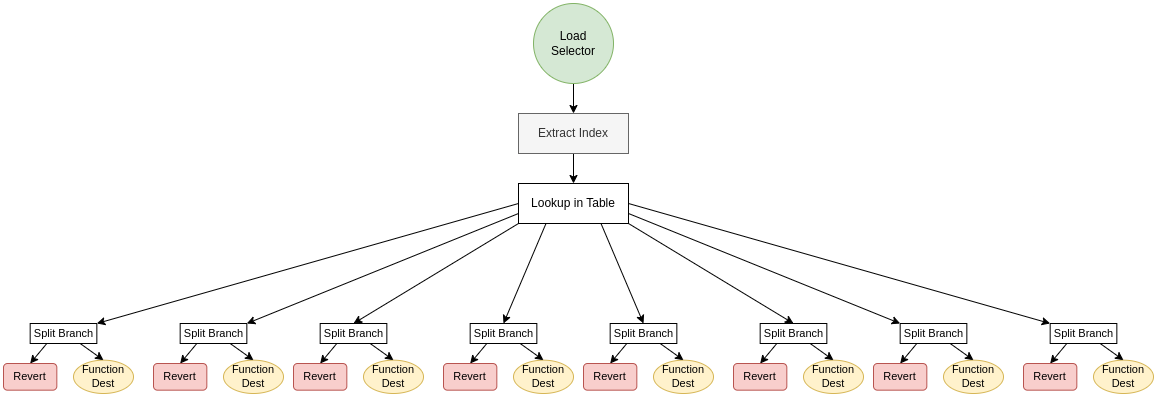

Binary Search Distpachers

The binary search based selector switch is much more efficient than the simpler linear else-if switch for contracts with more functions. This is achieved by structuring the switch like a binary search tree, eliminating half the possible selectors at every step. This makes the time complexity logarithmic, $O(\log n)$:

Intuitively we can see that the average gas cost of reaching any given method in the contract grows logarithmically relative to the number of selectors because we can double the number of supported selectors while just adding a constant size step on the path to every selector:

(click to expand)

Instead of 2 x “Split” and 1x “If-Else” branches, you need to traverse 3x “Split” and 1x “If-Else” branch to reach any given function. If the amount of functions is not a power of 2 the tree approach will still work but the number of branches required to reach a given function will vary.

But how does it work exactly? How are you able to eliminate half the possible functions at every step?

Like a binary search tree for integers, you can create one for the selectors of the functions and then compare them with some middle value at every node. This is possible because the EVM has no notion of datatypes, it doesn’t differentiate between strings, unsigned integers, signed integers, booleans, selectors or jump labels. To the EVM opcodes, all values on the stack are 256-bit words, that can be added, subtracted and compared, against each other. To create our selector binary search tree we first need to interpret the 4-byte selectors as integers and sort them:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

0x06fdde03 // name()

0x095ea7b3 // approve(address,uint256)

0x18160ddd // totalSupply()

0x205c2878 // withdrawTo(address, uint256)

0x23b872dd // transferFrom(address,address,uint256)

0x2e1a7d4d // withdraw(uint256)

0x313ce567 // decimals()

0x3644e515 // DOMAIN_SEPARATOR()

0x4a4089cc // withdrawFromTo(address, address, uint256)

0x70a08231 // balanceOf(address)

0x7ecebe00 // nonces(address)

0x87f8ab26 // depositAmount(uint256)

0x9470b0bd // withdrawFrom(address, uint256)

0x95d89b41 // symbol()

0xa9059cbb // transfer(address, uint256)

0xac9650d8 // multicall(bytes[])

0xb2069e40 // depositAmountTo(address, uint256)

0xb760faf9 // depositTo(address)

0xd0e30db0 // deposit()

0xd505accf // permit(address, address, uint256, uint256, uint8, bytes32, bytes32)

0xdd62ed3e // allowance(address, address)

You then continuously split the list of selectors in halves, saving the midpoints as you go along, so that you can construct the tree:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

0x06fdde03 // name()

0x095ea7b3 // approve(address,uint256)

<---- Split 1_1_1 0x10000000

0x18160ddd // totalSupply()

0x205c2878 // withdrawTo(address, uint256)

<---- Split 1_1_1_2 0x23000000

0x23b872dd // transferFrom(address, address, uint256)

0x2e1a7d4d // withdraw(uint256)

<---- Split 1_1 0x30000000

0x313ce567 // decimals()

0x3644e515 // DOMAIN_SEPARATOR()

<---- Split 1_1_2 0x40000000

0x4a4089cc // withdrawFromTo(address, address, uint256)

0x70a08231 // balanceOf(address)

0x7ecebe00 // nonces(address)

<---- Split 1 0x80000000

0x87f8ab26 // depositAmount(uint256)

0x9470b0bd // withdrawFrom(address, uint256)

<---- Split 1_2_1 0x95000000

0x95d89b41 // symbol()

0xa9059cbb // transfer(address, uint256)

0xac9650d8 // multicall(bytes[])

<---- Split 1_2 0xb0000000

0xb2069e40 // depositAmountTo(address, uint256)

0xb760faf9 // depositTo(address)

<---- Split 1_2_2 0xc0000000

0xd0e30db0 // deposit()

0xd505accf // permit(address, address, uint256, uint256, uint8, bytes32, bytes32)

0xdd62ed3e // allowance(address, address)

The code then compares the selector to the mid value to see if it should jump left or right at every point:

Smol Optimization Tip

Depending on the context within the code you can save gas by replacing

0x00(which compiles toPUSH1 0x00and costs 3 gas) with other opcodes that cost 2 gas and return0x00:

PC(program counter): Returns 0 if it’s the very first byte of your contractRETURNDATASIZE: Returns 0 until your contract has called another contract and the return / revert data was at least 1 byte long at which point it’ll return the length in bytes of that returned dataCALLVALUE: Returns 0 if no ETH was sent along with the call, if you’ve already done a call value check (assert(msg.value == 0)) you can rely on theCALLVALUEopcode to always return0until the end of the call.MSIZE(memory size): Returns 0 as long as you haven’t used memory yetNote that this is no longer necessary on chains with the Shanghai upgrade as you can just use the

PUSH0opcode which will always cost 2 gas and push 0 onto the stack regardless of context.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

// -- Get 4 byte selector

pc calldataload 0xe0 shr // [selector]

// -- Split 1

// Copy selector

dup1 // [selector, selector]

// Push split value of split 1

0x80000000 // [split_1_val, selector, selector]

// Compare selector to split value.

lt // [split_1_val < selector, selector]

// Prepare split 1_2 dest in case branching off.

split_dest_1_2 // [split_dest_1_2, split_1_val < selector, selector]

// Jump to split 1_2 if comparison succeeded

jumpi // [selector]

// Split 1_1

dup1 0x30000000 lt split_dest_1_1_2 jumpi

// Split 1_1_1

dup1 0x10000000 lt split_dest_1_1_1_2 jumpi

// Split 1_1_1_1

dup1 0x06fdde03 eq name_dest jumpi

dup1 0x095ea7b3 eq approve_dest jumpi

returndatasize returndatasize revert

split_dest_1_1_1_2:

// Split 1_1_1_2

dup1 0x23000000 lt split_dest_1_1_1_2_2 jumpi

// Split 1_1_1_2_1

dup1 0x18160ddd eq totalSupply_dest jumpi

dup1 0x205c2878 eq withdrawTo_dest jumpi

returndatasize returndatasize revert

split_dest_1_1_1_2_2:

// Split 1_1_1_2_2

dup1 0x23b872dd eq transferFrom_dest jumpi

dup1 0x2e1a7d4d eq withdraw_dest jumpi

returndatasize returndatasize revert

split_dest_1_1_2:

// Split 1_1_2

dup1 0x40000000 lt split_dest_1_1_2_2 jumpi

// Split 1_1_2_1

dup1 0x313ce567 eq decimals_dest jumpi

dup1 0x3644e515 eq DOMAIN_SEPARATOR_dest jumpi

returndatasize returndatasize revert

split_dest_1_1_2_2:

// Split 1_1_2_2

dup1 0x4a4089cc eq withdrawFromTo_dest jumpi

dup1 0x70a08231 eq balanceOf_dest jumpi

dup1 0x7ecebe00 eq nonces_dest jumpi

returndatasize returndatasize revert

split_dest_1_2:

// Split 1_2

dup1 0xb0000000 lt split_dest_1_2_2 jumpi

// Split 1_2_1

dup1 0x95000000 lt split_dest_1_2_1_2 jumpi

// Split 1_2_1_1

dup1 0x87f8ab26 eq depositAmount_dest jumpi

dup1 0x9470b0bd eq withdrawFrom_dest jumpi

returndatasize returndatasize revert

split_dest_1_2_1_2:

// Split 1_2_1_2

dup1 0x95d89b41 eq symbol_dest jumpi

dup1 0xa9059cbb eq transfer_dest jumpi

dup1 0xac9650d8 eq multicall_dest jumpi

returndatasize returndatasize revert

split_dest_1_2_2:

// Split 1_2_2

dup1 0xc0000000 lt split_dest_1_2_2_2 jumpi

// Split 1_2_2_1

dup1 0xb2069e40 eq depositAmountTo_dest jumpi

dup1 0xb760faf9 eq depositTo_dest jumpi

returndatasize returndatasize revert

split_dest_1_2_2_2:

// Split 1_2_2_2

dup1 0xd0e30db0 eq deposit_dest jumpi

dup1 0xd505accf eq permit_dest jumpi

dup1 0xdd62ed3e eq allowance_dest jumpi

returndatasize returndatasize revert

Unlike the diagram, you’ll notice that I didn’t create split branches all the way down, but instead put small linear switches at the end once only 2-3 functions were left in the split. This is because a split branch can only cut the range of selectors in half but cannot confirm whether the selector matches exactly, you need a directly comparing “if-else” branch at the end of your tree. If you split your selectors until each split only contains 1 selector the last split is redundant:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

// Split branch cost: 22 (+1 for jump dest on the `_2` branch)

// If-else branch cost: 22

// Split until only 1 Selector left

split_dest_x:

dup1 0xd2000000 lt split_dest_x_2 jumpi

// Split x_2

dup1 0xd0e30db0 eq deposit_dest jumpi (y + 44 gas to reach)

split_dest_x_2:

// Split x_2

dup1 0xd505accf eq permit_dest jumpi (y + 45 gas to reach, includes 1 gas for `JUMPDEST`)

// Linear if-else for 2 functions:

split_dest_x:

dup1 0xd0e30db0 eq deposit_dest jumpi (y + 22 gas to reach)

dup1 0xd505accf eq permit_dest jumpi (y + 44 gas to reach)

Similar reasoning applies to a split with 3 selectors. Further splitting a split with 3 selectors left turns the cost of (22, 44, 66) => (45, 66, 67). In fact, if you take the average gas use of the different selectors it doesn’t even make sense to break up a split containing 4 selectors: (22, 44, 66, 88; avg: 55) => (44, 66, 45, 67; avg: 55,5). Meaning that my example is not even a perfectly optimal binary search switch.

The Solidity compiler will automatically create such binary search switches once you have sufficient functions to justify the cost. Unfortunately, this is where we meet the limits of existing high-level compilers in terms of selector switch generation, to squeeze more gas out of our contracts we must dive deeper, into the dark depth of opcode-level optimization, but don’t worry it’s less intimidating than it sounds.

⚡Constant Gas Switches

Considering that the generated binary search switches are already optimal in terms of opcode use we need a completely different approach if we’re going to improve the gas cost of existing selector switches. To do that we’ll target the theoretically optimal time complexity of $O(1)$ meaning the cost of our selector switch doesn’t grow at all relative to the number of selectors.

While $O(1)$ is theoretically optimal we’ll also have to make sure the constant amount of gas used is actually cheaper than an alternative binary search or linear if-else switch. This is important because a naive $O(1)$ switch would e.g. be to store all jump destinations of the different functions in storage mapping-type data structure and load them when the contract gets executed, while this would use a constant amount of gas regardless of how many functions you have because it only needs a single SLOAD, the cost of that operation (2100) would make it more expensive than nearly any alternative.

🧱 Base Cost

Whenever I work on gas optimization I like to determine or at least approximate how efficient a solution could theoretically be. For gas cost this is usually down to what you need the code to do and what you’re working with. In general, when building a selector switch there are two pieces that cannot be avoided:

- Isolating the selector from calldata:

<zero push> calldataload+ [PUSH1 0xe0 SHR/PUSH32 0xffffffff00000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000 AND] (11 gas, assuming the zero-push is a 2 gas opcode such asPC,RETURNDATASIZEorPUSH0itself) - Checking if the selector is an exact match:

PUSH4 <expected_selector>[eq/sub]PUSH1/2 <code / revert dest> JUMPI(19 gas)

So we can confidently say that no ABI compliant selector switch, that reverts upon unmatching selectors can cost less than 30 gas. In fact, exactly 30 gas is possible when your contract has exactly 1 selector:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

// Load selector

pc calldataload 0xe0 shr

// Use subtraction opcode `SUB` as "not equals" comparison. If selectors don't match

// subtraction result will be non-zero and cause `JUMPI` to jump to the revert

<single_selector> sub no_match_error jumpi

// Huff macro that will insert the function's code

SINGLE_FUNCTION()

no_match_error:

returndatasize returndatasize revert // pushes 2 zeros and then reverts

Constant-lookup Data Structures

When it comes to looking up data based on some key in constant time the two main data structures that come to mind are arrays and hash maps. Since the EVM does not offer a native map / array opcode (yet), we’ll look at different ways we can build these data structures using the building blocks provided by the EVM.

Selector Indexing

Considering that jump labels are 2 bytes large and selectors are 4-byte (32-bit) large values that would require an 8.5GB array or map (2 ** 32 * 2) so that every single selector can be mapped to a unique jump label. To reduce the size of our lookup table and make it fit into the 24kB Spurious Dragon contract size limit we’ll need to extract an index that sits in a smaller range, however, this means that different selectors will result in the same index. This is why the final, 19-gas direct selector comparison is necessary as we need to rule out collisions to make sure that when our contract is called with a selector that’s not part of the ABI it’ll actually revert:

There are different ways to extract a unique index from the 4-byte selector:

Hashing

Hashing is the most general-purpose way to map a set of selectors to a unique set of indices in a tight range. One just needs to search for a nonce that when hashed together with the selector results in a unique index (mod n). While it may require some longer searching for larger selector sets the search time can be reduced by increasing the accepted output range for indices. Code for such an index extractor would look something like this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

// Gets selector.

pc calldataload 0xe0 shr // [selector]

// Combine nonce with selector, `nonce` should be a number shifted left by 32 to ensure

// it doesn't overlap with the actual selector.

dup1 [NONCE] or // [hash_preimage, selector]

// Store in memory for hashing.

msize mstore // [selector]

msize returndatasize sha3 // [hash, selector]

[MASK] and // [index, selector]

While this approach is quite general-purpose it’s not very efficient. With the required memory and SHA3 opcode use it brings the base cost of this approach to 93 gas, not including the code to do the table lookup. Meaning it’ll only really pay off when your contract starts to have >25 (or >40) functions, depending on the type of lookup table you’re using.

That’s why as an alternative to hashing it can be cheaper to make a custom “hashing function” that condenses the selector to an index by combining bitwise-xor, bit-shifting and modulus operations in a more creative fashion. Either approach will require you to iterate through many combinations to find the most efficient setup.

However, if you’re lucky and your selector set is smaller you can also use one of the following, more efficient selector indexing approaches:

Direct Bit-Masking

Looking at the selectors of the functions in your ABI as 32-bit binary values you can look to identify a set of bit positions across a tight range that are unique to all selectors e.g.:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

xx xxx

[0x06fdde03] 00000110111111011101111000000011 - {00___011} name()

[0x95d89b41] 10010101110110001001101101000001 - {01___111} symbol()

[0x313ce567] 00110001001111001110010101100111 - {11___100} decimals()

[0x18160ddd] 00011000000101100000110111011101 - {01___000} totalSupply()

[0x23b872dd] 00100011101110000111001011011101 - {10___110} transferFrom(address,address,uint256)

[0xa9059cbb] 10101001000001011001110010111011 - {10___100} transfer(address, uint256)

[0x70a08231] 01110000101000001000001000110001 - {11___010} balanceOf(address)

[0x095ea7b3] 00001001010111101010011110110011 - {00___101} approve(address,uint256)

[0xdd62ed3e] 11011101011000101110110100111110 - {01___101} allowance(address, address)

[0xd0e30db0] 11010000111000110000110110110000 - {01___011} deposit()

[0xb760faf9] 10110111011000001111101011111001 - {11___101} depositTo(address)

[0x2e1a7d4d] 00101110000110100111110101001101 - {10___000} withdraw(uint256)

[0x853828b6] 10000101001110000010100010110110 - {00___100} withdrawAll()

[0xca9add8f] 11001010100110101101110110001111 - {00___010} withdrawAllTo(address)

[0x205c2878] 00100000010111000010100001111000 - {10___001} withdrawTo(address, uint256)

[0x9470b0bd] 10010100011100001011000010111101 - {01___001} withdrawFrom(address, uint256)

[0x4a4089cc] 01001010010000001000100111001100 - {00___001} withdrawFromTo(address, address, uint256)

[0x3644e515] 00110110010001001110010100010101 - {11___001} DOMAIN_SEPARATOR()

[0x7ecebe00] 01111110110011101011111000000000 - {11___011} nonces(address)

[0xd505accf] 11010101000001011010110011001111 - {01___100} permit(address, address, uint256, uint256, uint8, bytes32, bytes32)

[0xac9650d8] 10101100100101100101000011011000 - {10___010} multicall(bytes[])

In the above example, there’s a set of 5-bits in an 8-bit range that are unique across all selectors. The tight range is ideal as it means the range of values between the lowest and highest index is not so wide and the table in our contract can therefore be smaller. Extracting the index from a selector would require the operator (selector >> MAGIC_SHIFT) & MAGIC_MASK which for the above example would be (selector >> 22) & 0xc7. In Huff:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

// Gets selector.

pc calldataload 0xe0 shr // [selector]

// Selector copied onto stack because it would be needed for direct comparison later

dup1 // [selector; selector]

0x16 shr 0xc7 and // [index ∈ (0x00,0xff); selector ]

Bit Splicing

While there will always be a set of bit indices that are unique across all selectors they may not always be across a tight range, in fact, it becomes increasingly less likely as the number of functions in your contract increases. This presents an issue as the resulting index needs to be in a tight range for the table size to be practical. However, there are a few tricks you can use to bring bits together that aren’t close to each other.

As an example let’s Imagine you have an ABI such that the set of unique bits across all selectors looks as follows (marked by X):

0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 X X X X 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 X 0 X 0 0 0 0 0 0

Extracted with the code: SELECTOR() 0x6 shr 0x3c005 and, representing a range of 18 bits. However, we can add a few simple operations to close the gap between the upper bits and the lower bits. By shifting and then bitwise OR-ing the values together we can create a resulting index that will always be in a smaller range:

1

2

3

4

5

Initially extracted: A B C D 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 E 0 F

Shifted right by 11: 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 A B C D 0 0 0

--------------------------------------------------------

OR-ed together : A B C D 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 A B C D E 0 F

Lower bits masked : 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 A B C D E 0 F

With just 3 operations (shift, or, and) we reduced the range of the resulting index while keeping the unique bits, in Huff this would look like this (0xb is 11 in hexadecimal):

1

2

3

4

5

6

// Gets selector.

pc calldataload 0xe0 shr // [selector]

dup1 0x6 shr 0x3c005 and // [wide_index, selector]

dup1 0xb shr // [shifted_top_bits, wide_index, selector]

or 0x7f and // [narrow_index, selector]

This is quite efficient as it doesn’t use a lot of opcodes and they’re all base-2 operations (bit-wise OR, bit-shift, bit-wise AND) which cost 3 gas vs. other arithmetic operations like mod, div and mul which could also be used but cost 5 gas each.

🏗️ Building Lookup Tables in the EVM

Similar to how there are several approaches with varying efficiencies when building a selector indexer there are also several approaches to building and retrieving values from lookup tables.

Push Tables

With these tables, you can pack up to 16x 2-byte jump destinations into a single value and then have the table be pushed in its entirety onto the stack using a PUSH opcode. This is quite efficient as “loading” the table itself only requires 3 gas and retrieving a value 12 gas, assuming your index is already multiplied by 16 to ensure it’s a useful offset. The big constraint with this approach is that it only supports indices that are in the range 0-15 which will be an issue if your contract has more than 16 functions that need to be jumped to. Assuming you’re able to find a group of 4-bits that is unique across all selectors the switch would look as follows:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

// Gets selector.

pc calldataload 0xe0 shr // [selector]

[JUMP_TABLE] // [table]

dup2 [IND_SHIFT] shr // [shifted_selector, table, selector]

// Mask offset by 4 bits to ensure the result will be a valid table shift.

0xf0 and // [index, table, selector]

shr 0xffff and // [jump_dest, selector]

jump

// At the jump destinations, check if selector matches:

0x???????? sub error_dest jumpi

FUNCTION_LOGIC()

error_dest:

0x0 0x0 revert

You can fit more than 16 labels into a push table if each label is smaller than 16 bits. This will almost certainly be the case as the current contract size limit is 24kB meaning the largest realistic jump destination would only require 15 bits. Depending on your contract size your jump labels may take up even less space. However, an important thing to note is that if the bit size of your labels is not a power of 2 you’ll need an additional push and multiplication operation to compute the shift for the lookup. Example with jump label size of 12-bits (0xc in hexadecimal):

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

// Gets selector.

pc calldataload 0xe0 shr // [selector]

[JUMP_TABLE] // [table]

dup2 [IND_SHIFT] shr // [shifted_selector, table, selector]

// Mask unique bits

0x1f and // [index, table, selector]

// Multiply by 12 to get the offset of the label

0xc mul // [label_offset, table, selector]

shr 0xfff and // [jump_dest, selector]

jump

// At the jump destinations, check if selector matches:

0x???????? sub error_dest jumpi

FUNCTION_LOGIC()

error_dest:

0x0 0x0 revert

Table Trees

Push tables can be extended to support even more functions by creating a shallow tree whereby the first table selects a sub-table that determines the final destination. While this is technically still a tree with logarithmic $O(\log n)$ time complexity, practically its time complexity is constant as you’ll never need a tree that’s deeper than 3 levels. Using such a tree makes selector indexing even easier as you don’t need to find a tight bit range that uniquely identifies all selectors but instead, you just need to find a smaller range that groups selectors in groups no larger than 16, with each group able to have their own range.

As an example imagine a contract with 128-functions:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

0x4482d182 0xf5d05a80 0x24ce2433 0x82c35051 0x9eb17fb7 0x4802a7fd 0x2c0e5bac 0xf8313123

0x4e2464cd 0x9d5f65e1 0x0fa9584d 0x6f019090 0xf4f3fbb8 0x29cd002a 0xb82bf507 0x4c0656c3

0xbd0a5449 0x59327a62 0x3c253f7f 0x969e72a9 0x0a7a2ceb 0x5c46eeab 0xac4ab926 0x84089c91

0x4dc74a98 0x55cac09d 0x02a69ada 0x5acc746b 0xebab72a8 0xce280460 0x5820c09a 0x522fecc8

0xced910c1 0xaed519b4 0xe850db0f 0x144db955 0x64a42fda 0xb569a22a 0x78890a44 0x96eb0ebc

0x237e81b6 0x605a6e34 0x63ae1af7 0x25a86543 0xd7d01f4a 0xf6763fed 0xc8fa772d 0x10897e4e

0xb85abce6 0xaa77f58e 0x3bedf0bb 0x149791ea 0x3eeb3d98 0xe59dc2db 0x063cdcb2 0xfadb4823

0xa008b45a 0xb84df3af 0x9fb39812 0xc8a0ebf2 0xe7ad912d 0x94a32c56 0xd2b1a96a 0xd4a8589d

0x4dd90963 0xb4830428 0x7cf58051 0x6573a075 0xcdc89bc1 0x7889cf21 0x03682317 0xc06a9ed2

0x46f2c6b0 0x06544126 0x078d22e1 0x4f492320 0xb6a69d6c 0x103eedc6 0x2f3cb837 0xeac9fedb

0xf6d647f0 0x6b0dc469 0x81a6d8df 0x2b2911a4 0x02e71741 0xc746d79d 0x0c97fce9 0xff4ab2e2

0xb83ac239 0x40341065 0x00bc2475 0x36dd0f40 0x378a6476 0x6491330a 0x8a104473 0x0d33ae64

0xb68734d9 0xde45a986 0xd70e58ee 0xebaf8b57 0xcc5ade18 0x94fbb841 0xcd42e3d1 0xb387c57a

0xde1e50f3 0x94a40bdf 0xc59f70c9 0x9ff884da 0xc3a075fe 0x81ebea85 0x75b569d7 0x07dcb7bf

0x30aa9aae 0x21770e06 0x88e13c98 0x9ff7735a 0x0d2c39db 0x656f06d0 0x5971a031 0x4925d035

0x042a2f53 0x50fce891 0xb673685b 0xa54741fc 0x9c527625 0xa55cf11c 0x2ba1c786 0x3bd3b8ec

You can then find a 4-bit mask that splits the selectors into distinct groups:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

root mask: 00000000000000000000000000001111

group (0000):

gmask: 00000000000000000000000001111000

[0xf5d05a80,0x6f019090,0xce280460,0x46f2c6b0,0x4f492320,0xf6d647f0,0x36dd0f40,0x656f06d0]

group (0010):

gmask: 00000000000000000000000011110000

[0x4482d182,0x59327a62,0x063cdcb2,0x9fb39812,0xc8a0ebf2,0xc06a9ed2,0xff4ab2e2]

group (0100):

gmask: 00000000000000000000000011110000

[0xaed519b4,0x78890a44,0x605a6e34,0x2b2911a4,0x0d33ae64]

group (0101):

gmask: 00000000000000001111000000000000

[0x144db955,0x6573a075,0x40341065,0x00bc2475,0x81ebea85,0x4925d035,0x9c527625]

group (0110):

gmask: 00001111000000000000000000000000

[0xac4ab926,0x237e81b6,0xb85abce6,0x94a32c56,0x06544126,0x103eedc6,0x378a6476,0xde45a986,0x21770e06,0x2ba1c786]

group (0111):

gmask: 00000000000000000000000011110000

[0x9eb17fb7,0xb82bf507,0x63ae1af7,0x03682317,0x2f3cb837,0xebaf8b57,0x75b569d7]

group (1000):

gmask: 11110000000000000000000000000000

[0xf4f3fbb8,0x4dc74a98,0xebab72a8,0x522fecc8,0x3eeb3d98,0xb4830428,0xcc5ade18,0x88e13c98]

group (1001):

gmask: 00000000000000000000000011110000

[0xbd0a5449,0x969e72a9,0x6b0dc469,0x0c97fce9,0xb83ac239,0xb68734d9,0xc59f70c9]

group (1011):

gmask: 00000000000000000001111000000000

[0x0a7a2ceb,0x5c46eeab,0x5acc746b,0x3bedf0bb,0xe59dc2db,0xeac9fedb,0x0d2c39db,0xb673685b]

group (1100):

gmask: 00000000000000000000000011110000

[0x2c0e5bac,0x96eb0ebc,0xb6a69d6c,0xa54741fc,0xa55cf11c,0x3bd3b8ec]

group (1110):

gmask: 00000000000000000000000001111000

[0x10897e4e,0xaa77f58e,0xd70e58ee,0xc3a075fe,0x30aa9aae]

group (1111):

gmask: 00000000000000000001111000000000

[0x3c253f7f,0xe850db0f,0xb84df3af,0x81a6d8df,0x94a40bdf,0x07dcb7bf]

Table in Code

As an alternative to using the PUSH opcode to store & load lookup tables, which limits you to 32 bytes at a time you can store larger lookup tables directly in the bytecode and load the target label with CODECOPY. In Huff this is enabled by the jump-table syntax:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

// Example for non-packed table from Huff's docs

#define jumptable SWITCH_TABLE {

jump_one jump_two jump_three jump_four

}

// Packed version

#define jumptable__packed SWITCH_TABLE_TIGHT {

jump_one jump_two jump_three jump_four

}

#define macro MAIN() = takes(0) returns(0) {

// Push bytecode offset of table onto the stack

__tablestart(SWITCH_TABLE)

}

While this approach lends itself well to larger selectors sets it does use more gas than a 1-level push table as you need to copy the jump dest into memory using CODECOPY and then load it using MLOAD.

🏃 Code as Table / Direct Jumping

Instead of looking up the jump destination based on some derived index you could directly convert it to a jump destination and jump to it. To do this the jump destinations should be evenly spaced so that the index can easily be converted to a jump dest: jump_dest = index * dest_spacing + offset. Even spacing comes at the large downside of increased bytecode size as you’ll need to pad the bytecode of all your methods to be as large as your largest method:

In Huff:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

GET_SELECTOR() // [selector]

dup1 GET_IND() // [index, selector]

[SPACING] mul [OFFSET] add // [jump_dest, selector]

jump

// Code At every function

// Label required in Huff to ensure `JUMPDEST` is generated during compilation

// otherwise dynamic `JUMP` will revert

fn1:

// '0x????????' represents the expected selector

0x???????? sub revert_dest jumpi

// Actual function logic

// Bytecode padding (simplest being 0-bytes which are interpreted as stop opcodes)

stop stop // ......

revert_dest:

0x0 0x0 revert

Depending on your chosen selector indexing method, entire code sections may have to be empty with only a revert at the beginning to catch incorrect selectors. The “Selector Check” code ensures that the selector is actually part of the ABI and didn’t just e.g. have the same bits as a different valid selector.

Saving on Padding by rearranging code:

Instead of having the different functions have the same bytecode size we can move up the selector-check code and pad those instances instead of the actual functions to massively reduce the overall bytecode. This can be crucial because depending on the size of functions and index range it may not even be feasible to pad functions. Since the selector-check utilizes a JUMPI-op anyway the destination can simply be set to the actual functions instead of the revert code. This does however add 1 gas to the runtime gas cost due to the added JUMPDEST. Rearranging the code makes it look like this:

The blocks are not meant to be an accurate, proportional display of bytecode size but rather a rough, visual representation

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

GET_SELECTOR() // [selector]

dup1 GET_IND() // [index, selector]

[SPACING] mul [OFFSET] add // [jump_dest, selector]

jump

// For every possible destination:

dest1:

0x???????? eq fn1 jumpi

0x0 0x0 revert

dest2:

0x???????? eq fn2 jumpi

0x0 0x0 revert

dest3:

0x0 0x0 revert

stop stop stop stop stop stop stop stop stop stop

// (10-bytes padding required to match `PUSH4 <4x?> EQ PUSH2 <2x?> JUMPI`)

dest4:

0x???????? eq fn3 jumpi

0x0 0x0 revert

fn1:

// Code for function 1

fn2:

// Code for function 2

fn3:

// Code for function 3

The packed block of selector-checks and reverts is also why I like to call this approach the “code as table” approach because while it’s not exactly a lookup table, the contract’s code acts like one by translating the initial jump to the final destination through its execution.

Bringing it Together

When building selector switches the main tradeoff will be between gas efficiency and code size. Without sacrificing too much in code size you can already have large gains in gas efficiency, especially for contracts with larger selector sets. To save even more gas you could sacrifice collision resistance, removing the selector-check. However, I’d highly discourage this as it may lead to vulnerabilities in interacting contracts that expect external contracts to revert for calls to unsupported methods.

To build constant gas function dispatchers for your contracts you’ll have to carefully compare and test different combinations of components to find what best suits your needs.

💫 Special Branches

💵 Payable Functions

Beyond simply checking the selector and identifying the section of code that belongs to the function you may also want your function dispatcher to check the call’s msg.value (aka callvalue). There are several reasons why it’s beneficial from an optimization perspective to put callvalue checks in the function dispatcher:

- It can make the

require(msg.value == 0)check for non-payable functions cheaper - It’ll help the dispatcher route to payable methods more efficiently

Binary Search Function Dispatchers

For a binary search function dispatcher you can put a branch checking the callvalue at the very beginning:

The

JUMPIopcode jumps to the target destination whenever the condition value on the stack is non-zero. This means you don’t have to waste gas addingISZERO ISZEROprior to aJUMPIfor condition values that may be >1. This fact also allows you to save gas in certain situations by inverting conditions via the removal of a singleISZEROand swapping the code that is present after theJUMPIand at theJUMPDEST.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

// load selector

pc calldataload 0xe0 shr

callvalue payable_fn_tree jumpi

// binary search function dispatcher with only 0-ETH functions

payable_fn_tree:

// binary search function dispatcher with only ETH-accepting functions

This will make your contract smaller as you won’t have to repeat callvalue checking code for every function and it’ll make payable functions cheaper as it’ll shorten the path to the payable functions when value is sent. What you also have to be careful of is if your payable functions are also meant to be able to not accept ETH, i.e. being executed when msg.value == 0. If you don’t include the selectors of the payable functions in the non-payable side of the tree you won’t be able to call the methods without callvalue; this may be desirable in some cases.

Constant Gas Function Dispatchers

Depending on your selector indexer you may not necessarily want to put your callvalue check at the beginning of your contract. This is because it’ll add the check to the execution flow of all functions regardless if they’re payable or not. By only adding the check to the non-payable methods you’ll make payable functions cheaper. You can easily use the same JUMPI from the selector check for the callvalue check:

1

2

3

4

5

selector_check_dest:

<expected_selector> eq // [selector == expected_selector ? 1 : 0]

callvalue lt // [msg.value < selector == expected_selector ? 1 : 0]

<final_function_dest> jumpi

returndatasize returndatasize revert

This above code works because the result of EQ in the EVM is either 0 or 1, meaning that the resulting condition value can only be 1 if both the selector matched and the msg.value is strictly less than 1, meaning 0. If the selectors don’t match there’s no msg.value that’ll satisfy the LT(CALLVALUE(), EQ(...)) comparison. This selector check block is great because it’s exactly 16 bytes large (assuming 2-byte jump dest and 4-byte selector) allowing you to use cheaper base-2 operations to convert your index into the jump destination.

Fallback Functions

Receive fallback

The receive fallback function is typically used to accept ETH via empty calls. In Solidity it’s defined with the receive keyword:

1

2

3

receive() payable external {

// ...

}

To check whether the current call is to the receive fallback function you can treat it like a call with the 0x00000000 selector but no calldata i.e. a CALLDATASIZE of 0. This is because in the EVM if you try to read calldata beyond what was actually provided via CALLDATALOAD or CALLDATACOPY the EVM will pad the result with 0x00-bytes. Meaning that our selector extracting code pc calldataload 0xe0 shr will place a 0 on the stack when the calldata is empty, the same as if you were to call the contract with the actual zero selector 0x00000000. So how do you differentiate these cases? As previously eluded to, CALLDATASIZE will push the length of calldata to the stack, this allows you to easily check which is which (if you have both in your contract):

1

2

calldatasize iszero receive_fn jumpi

dup1 0x00000000 eq zero_selector_fn jumpi

The fact that 0 is pushed to the stack as the selector for the receive fallback is especially useful for constant gas dispatchers as you don’t have to change your selector indexer or table lookup for it. The only change required is the final selector check which can be changed from being selector based to calldatasize.

Fallback-Fallback

The fallback-fallback function is the function called when nothing else matches and in Solidity it accepts arbitrary calldata. Generally, I’d heavily discourage the use of the fallback method, unless you’re writing a base proxy contract as it creates a foot gun other developers could step into. Multicoin’s bridge was exploited precisely because they were not expecting WETH9’s silent fallback function. Therefore I won’t go too much into it but essentially if you need a fallback function you just need to change the 0x0 0x0 revert at the end of all branches to a fallback jump to ensure that all code paths continue in the fallback function if an appropriate selector was not found.

METH’s Constant Gas Function Dispatcher

For METH, I built a practical 23-function (24 if you count the receive fallback), constant* gas function dispatcher that costs about half what the average cost for a normal binary search function dispatcher would be. I put an asterisk next to the “constant” because the cost isn’t the same for all functions:

| Category | Gas Cost |

|---|---|

| Receive Fallback | 54 |

| Payable Functions | 55 |

| Non-payable Functions | 60 |

Note: the gas cost does not include the cost to read the selector as I don’t consider that part of the “dispatcher” and it’s required regardless of the type of dispatcher you create.

Update: The above gas cost figures are no longer fully accurate for METH’s function dispatcher. This is because for certain methods with checks e.g.

transfer, METH now combines the selector-check with the balance-check to save on gas by reducing the amount of uniqueJUMPIinstructions. The cost of theJUMPIis therefore no longer solely carried by the dispatcher and is in practice reduced depending how you want to attribute its costs.

The dispatcher is so efficient because of how the selectors are laid out. Specifically, the highest 8-bits of the selectors are unique for all functions. 8-bits or 0-255 is a small enough range where the locations for the selector checks still fit into the 24kB contract size limit. The unique bits being the highest also means I only need to shift and mask the value once to extract the index, clear the dirty bits and construct the jump destination:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

pc calldataload 0xe0 shr // [selector]

dup1 // [selector; selector]

// Shift right by 20 to preserve the 12 topmost bits

0x14 shr // [sbits ∈ (b000000000000, b111111111111); selector]

// Overwrite the lower 4 bits with 1, keeping only the unique upper 8 bits

0x0f or // [index * 16 + 15; selector]

// Jump to the created destination

jump

Using a bitwise-OR instead of AND to “clear” the lower bits is a cool trick in my opinion because it serves two purposes:

- It “evens out” the lower bits of the output value to ensure that the possible output values are evenly spaced out

- It ensures the minimum output value is

15orb1111, meaning the receive-fallback function and selectors with 8 zero upper bits can still result in a valid jump destination without having to use an additionalPUSH&ADDoperation.

I then use the “code as table” approach adding selector checks with the final destinations at all valid jump destinations and a simple JUMPDEST PUSH0 PUSH0 REVERT, with padding at all invalid destinations, encapsulated in the NO_MATCH macro. Here’s an excerpt from the Huff code:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

dest_0x18f: NON_PAYABLE_FUNC_CHECK(0x18160ddd, totalSupply_final_dest)

dest_0x19f: NO_MATCH()

dest_0x1af: NO_MATCH()

dest_0x1bf: NO_MATCH()

dest_0x1cf: NO_MATCH()

dest_0x1df: NO_MATCH()

dest_0x1ef: NO_MATCH()

dest_0x1ff: NO_MATCH()

dest_0x20f: NON_PAYABLE_FUNC_CHECK(0x205c2878, withdrawTo_final_dest)

dest_0x21f: NO_MATCH()

dest_0x22f: NO_MATCH()

dest_0x23f: NON_PAYABLE_FUNC_CHECK(0x23b872dd, transferFrom_final_dest)

dest_0x24f: NO_MATCH()

dest_0x25f: NO_MATCH()

dest_0x26f: NO_MATCH()

dest_0x27f: NO_MATCH()

dest_0x28f: PAYABLE_FUNC_CHECK(0x28026ace, depositAndApprove_final_dest)

dest_0x29f: NO_MATCH()

dest_0x2af: NO_MATCH()

dest_0x2bf: NO_MATCH()

dest_0x2cf: NO_MATCH()

dest_0x2df: NO_MATCH()

dest_0x2ef: NON_PAYABLE_FUNC_CHECK(0x2e1a7d4d, withdraw_final_dest)

The main downside to this function dispatcher is code size, with 256 possible destinations and each block being padded to 16 bytes large the function dispatcher alone is 4.1 kB large 🤯. However, this is a worthy tradeoff to me as the cost of the contract’s size is one-time and paid at deployment vs. the runtime gas cost which will continuously be paid by all users of METH.

Update: METH has moved to using the “padded function” approach whereby each destination is 64-bytes large, blowing up the contract’s size to 16kB (the majority of which is padding). This is mainly to allow for

JUMPIreuse between the selector-check and other checks. Due to certain functions being larger than 64-bytes they overflow into the next block meaning certain unimplemented selectors will revert exceptionally (using all gas) rather than being simply reverted.

Efficient Function Dispatchers Post EIP-4200

In the suite of upcoming EOF upgrades to the EVM, EIP-4200 proposes adding new jump opcodes to replace the existing JUMP, JUMPI and JUMPDEST opcodes that are responsible for branching and jumping in EVM contracts today. The RJUMP and RJUMPI opcodes are 1-to-1 replacements of the JUMP and JUMPI opcodes with a few minor differences: no JUMPDEST will be required at the destination (-1 gas), they’ll only accept static relative jump destinations that aren’t pushed (-3 gas) and each only cost 2 gas meaning direct jumps (RJUMP <dest> vs. PUSH <dest> JUMP ... JUMP) will be 10 gas cheaper and conditional jumps will be 12 gas cheaper. Note that the EIP is not yet final so the gas costs may change.

However, the EIP-4200 opcode that’ll have the biggest impact on function dispatchers in my opinion is the RJUMPV opcode. The RJUMPV opcode is intended to only cost 4 gas and acts as a jump table with up to 256 jump destinations (technically only 255 right now but I’ve proposed a change that’d allow up to 256). At runtime, the opcode would accept an index between 0-255 and then jump to the configured jump destination. The table doesn’t have to be 256 large and you can even leave “gaps” in the form of 0 offsets which will default to not jumping. The RJUMPV opcode would allow constant gas function dispatchers like METH’s to not only be cheaper but take up less bytecode. It’ll also make it easier for compilers of high-level languages like Solidity, Vyper, Fe, Sway, etc. to construct constant gas dispatchers in a generalized manner. This is because now the selector indexer can have an index range size of up to 256 at no big cost.

Conclusion

Function dispatchers are an important part of smart contracts and have so far remained relatively unexplored in the optimizooor space. Especially pre-EIP-4200 there’s a lot of room for clever tricks, optimizing the dispatcher of a larger contract can help shave 10, 20, 40+ gas from your contract which can be a lot in the land of hyper-optimized Huff contracts.

I hope this post was valuable to you, feel free to give your thoughts and feedback and follow me on my Twitter @real_philogy for more technical crypto content.

Footnotes

Joseph A. Carr, Attribution, via Wikimedia Commons ↩

Every contract written in high level languages that target the EVM like Solidity, Vyper, Fe have selector switches by default, however certain MEV bot contracts written in low level languages / assembly may omit an ABI compliant selector switch to save on even more gas. ↩